The Works of Kant

LMAVB RSS XVIII/138/1

In the early years of his career, Kant wrote strictly academic works. In 1764, however, he published an essay Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime, which brought him to the attention of the general public. Here, for example, Kant discusses such a popular question as the differences between the sexes. The category of beauty, he argued, is more inherent to women, while the category of the sublime is more inherent to men. That is why man and woman complement each other – they become almost one person, with the woman's intuition of beauty and the man's profound reason. Kant reasoned that we can also use these categories to better understand the differences between temperament models. For example, the melancholic lives in the realm of the sublime; the sanguine is much closer to beauty – s/he enjoys life and is open to change, but his/her moral principles are not stable; while the choleric exists in the realm of the superficial – for such a person appearance is much more important than reality. Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime ends with notes on the differences between national characters. So, although the title of the book suggests aesthetic issues, anthropology is at its centre.

LMAVB RSS XVIII/138/2

The book Dreams of a Spirit-Seer, Illustrated by Dreams of Metaphysics has two aims ¬– to discuss the visions of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) and to study the limits of metaphysics. The figure of E. Swedenborg was interesting to Kant because he was not a typical religious mystic. In the first half of his life, he was known for his work in mathematics, philosophy, mineralogy, mechanics and mining. However, at the age of 56, Swedenborg experienced a religious revelation. He began to have visions of dead souls, angels and God himself. Eventually he was said to have founded a new church. Swedenborg was also known for his prophecies, which were sometimes surprisingly accurate.

At first, Kant was fascinated by the stories of the new mystic, but eventually he became quite sceptical about his visions. Everything Swedenborg says is nothing but dreams and illusions – only naive people can believe in these fairy tales, was the philosopher's final conclusion. But if a rational person does not believe these stories, why should s/he believe books of metaphysics? These “visionaries of reason”, like ,,visionaries of feeling”, tend to confuse reality with their dreams. This was still 14 years before the publication of the Critique of Pure Reason, but Kant was already questioning the limits of our knowledge.

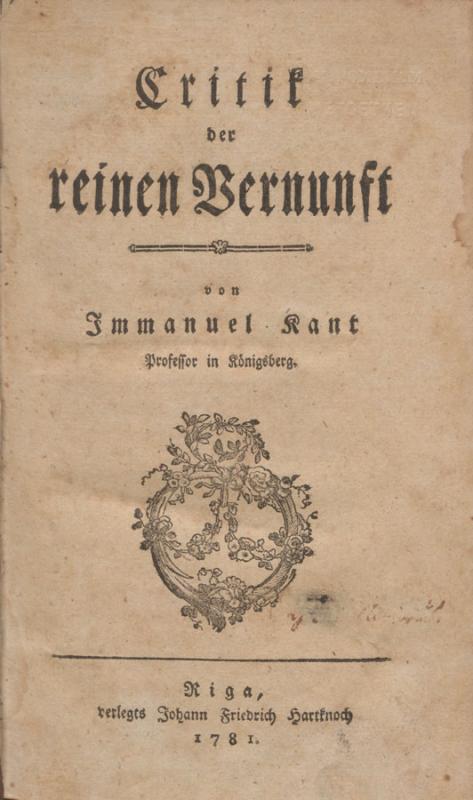

LMAVB RSS V-18/1-4244

How do we understand the physical world? How do we know that the mental copies of things that exist in our minds are correct? And if we have no criteria of truth, perhaps our whole life is just a dream? This is what the classical philosophical questions about the problem of knowledge looked like before the appearance of the Critique of Pure Reason. In this work Kant doesn't answer them, but he changes the way we ask them. Instead of asking, “How do we know something?” he asks, “What are the conditions under which our knowledge is possible?”. The most general answer to this question is extremely elegant and simple. First, we have no knowledge of things-in-themselves, but we are somehow influenced by them. Second, we perceive this influence through the “lens” of our reason. So, everything we perceive and know about the world is nothing but a mental construction. Kant's aim is to reveal the basic principles on which this is based. Space and time are the first forms that make us see things in a particular order. But how do we see them? We see them as having some identifiable qualities; we also see that there is some kind of interaction between them. All this is possible because of the categories of reason, such as quantity, unity, causality, and so on. In other words, the fact that we perceive an apple as having a particular shape, smell and weight, rather than conceiving of all these qualities as independent of each other, is only possible because our reason works in this way. Is such a picture of the world, correct? We don't know. Perhaps the real world is a mysterious x beyond the opposition of unity and plurality, perhaps our reason shows us different things only because it is nothing but a broken mirror showing fragments of reality. We don't know. When we try to answer these questions, we go beyond the limits of reason and enter the realm of dogmatism. It follows that true knowledge is confined to the limits of reason, and thus we are unable to ascertain the answer to the most fundamental metaphysical questions.

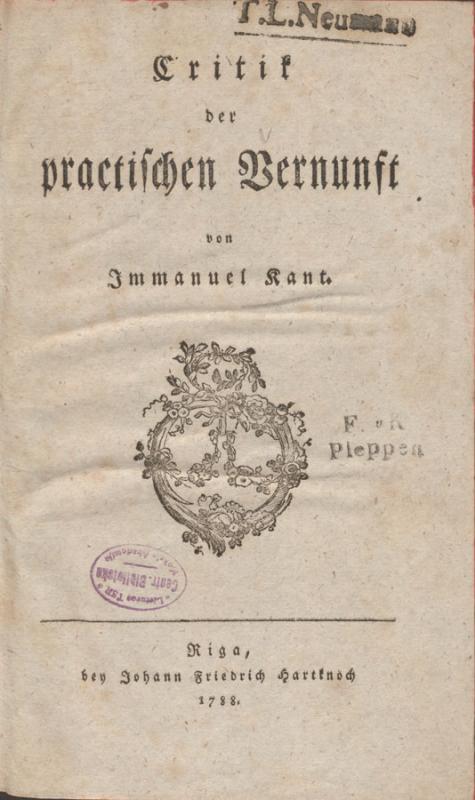

LMAVB RSS V-18/12378

Critique of Practical Reason is one of Kant's most important ethical works. It deals with the essential principles of ethical behaviour and discusses their conditions. What is the basis of morality? Freedom. If people are not free, then the choice between good and evil does not exist. But the problem is that it is impossible to prove that there is a real difference between good and evil, and of course it is impossible to prove that freedom itself is real. We simply state that such things exist. Why do we do this? There is no answer to this question in Kant's philosophy – he is not yet concerned with the genealogy of ethics, but asks what principle allows us to distinguish good from evil. It was in the context of this problem that the famous categorical imperative appeared: “act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law”. In other words, if you want your actions to be good, the principles of your behaviour should play the same role in the social world as the laws of nature play in the physical world. Are you committed to the ideal of a harmonious society? Do your principles guarantee the freedom of others? If the answer is no, then actions based on them are not moral. Moral actions cannot restrict the ethical freedom of others: “So act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means”. The only problem is that it is impossible to meet these requirements in full – we can at least try, but only if we believe that our souls are immortal and that there is a God who will give ethical individuals the greatest joy in heaven. These postulates may seem a concession to religion, but without them we must transform Kant's ethics into something more in tune with the cruel reality of the human world.

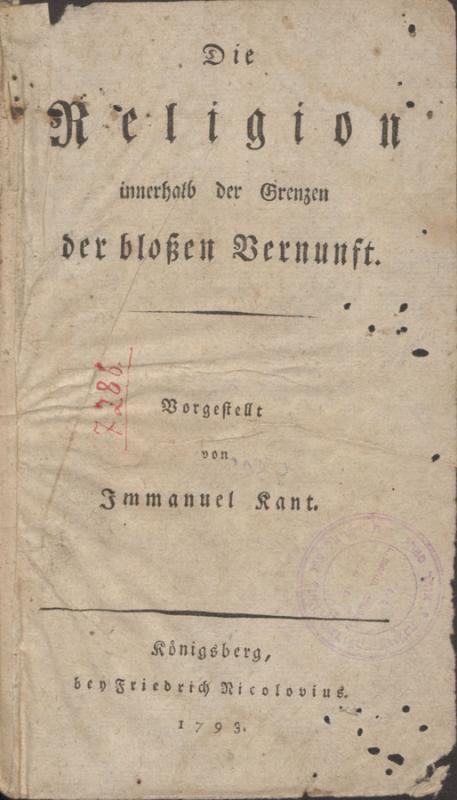

LMAVB RSS V-18/11643

The purity of Kant's ethics can give the impression that he tended to idealise human beings. But this impression disappears at second glance. Alongside the belief that human beings, as rational beings, should eventually create a harmonious society without wars and violence, Kant argues that human nature is “radically evil”. Only by confronting it with innate goodness can we hope for a better future for humanity. The tension between good and evil that tears human beings apart is the main problem of Kant's “Religion within the Bounds of Pure Reason”. Even the most ethical person is, after all, only human, which means that the ideal of the saint cannot be fully realised. Nevertheless, we should do everything possible to move in this direction, and, along with personal efforts to be a better person, one must seek a better organisation of society, since it has a huge influence on our behaviour. Ultimately, an ideal society should consist of individuals who do not believe in any authority, but who carry the moral law within themselves. It is this society that Kant calls the Church. The real service to God, Kant claims, is nothing but a moral life, while all the rituals and priests have nothing to do with it. No wonder such a position displeased the Prussian authorities, and, although Kant wasn’t prosecuted, he agreed not to speak further on religious matters.

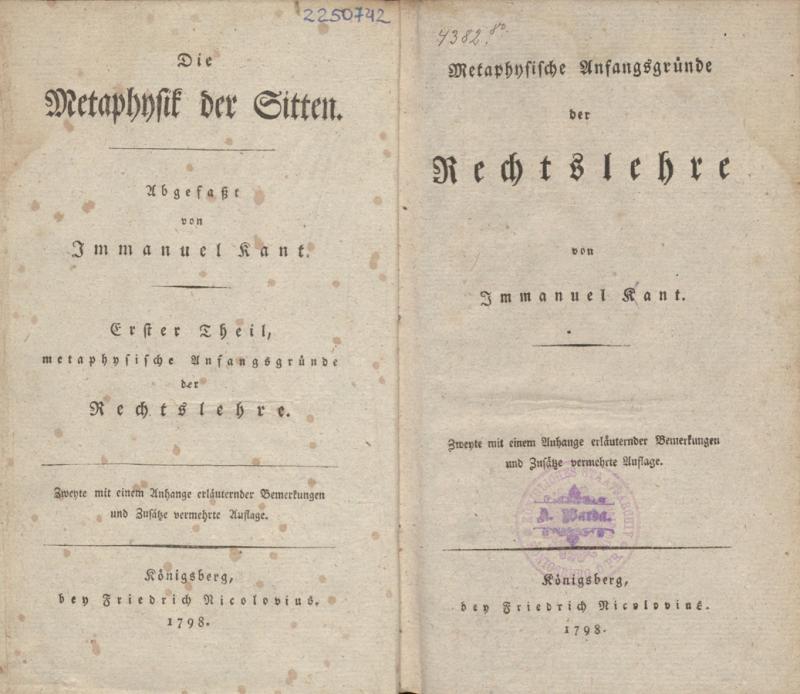

LMAVB RSS V-18/1-12881

The cornerstone of Kant's philosophy of law is his moral theory. All legal theory is based on the assumption that human beings are capable of making free choices. But if ethics is concerned with freedom understood as independence from one's desires, legal theory is concerned with freedom understood as self-will. Indeed, it is often nothing more than the ability to live according to one's desires that is understood as a free life. Since self-will knows no limits, we need the law. Thus, legal theory discusses the sum of conditions under which everyone's self-will is limited in the name of the freedom of others. And if ethics limits one “from within”, law, on the contrary, limits one “from without”. The ultimate goal of such “external” limitation is nothing less than a society in which morality can flourish to the full.

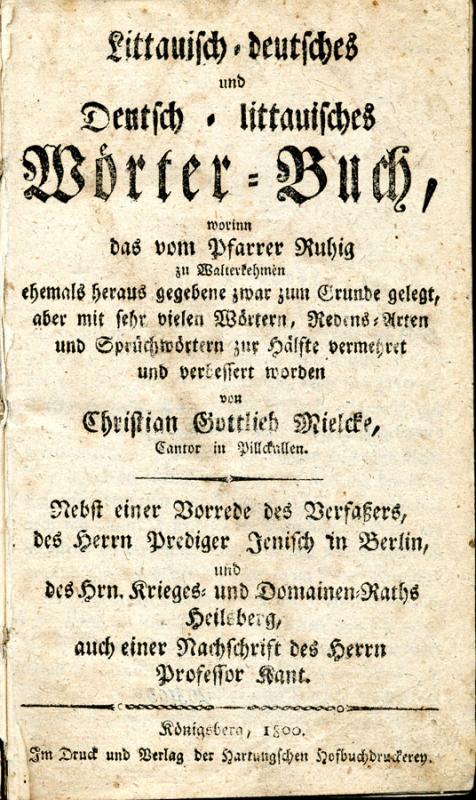

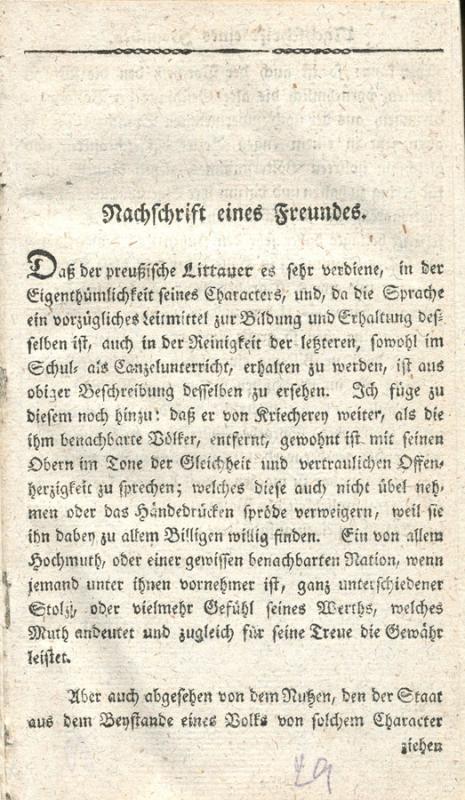

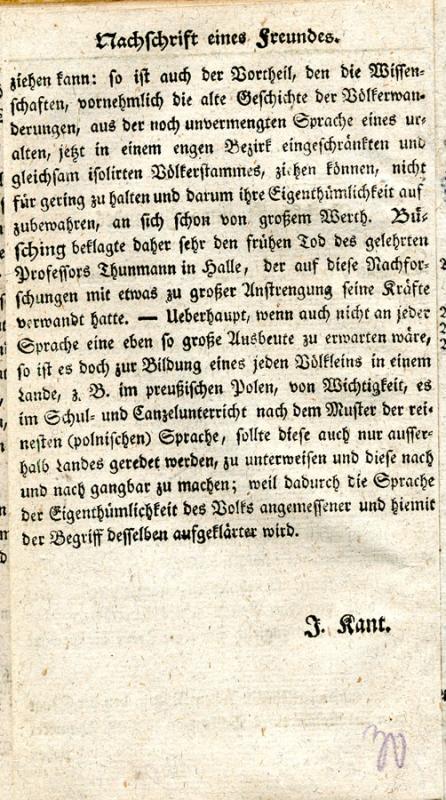

LMAVB RSS LK-18/5

In this text, Kant emphasised the importance of preserving the Lithuanian language, drew attention to its importance for humanities, compared the Lithuanians with the neighbouring Polish nation, and wrote that Lithuanians do not want to please, are brave, dignified and sincere. As historians have noted, these remarks can be considered one of the finest examples of this genre in Lithuanian literature.

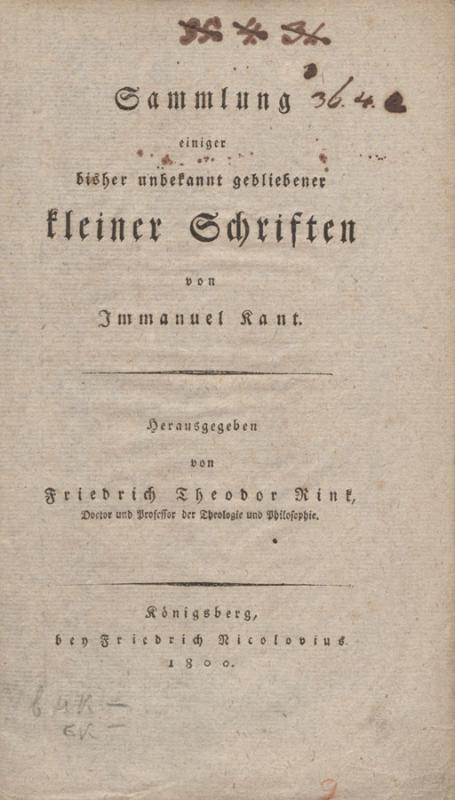

LMAVB RSS V-18/13618

Until 1838, there was no complete collection of Kant’s works in German. As a result, Kant’s writings prior to the publication of the Critique of Pure Reason were largely unknown. During Kant's lifetime, however, there were attempts by his students to fill this gap. The Compilation of some previously unknown small writings, published in 1800, was one of the steps towards a complete collection of Kant's works. However, despite the fact that the editor of these works (Friedrich Theodor Rinck, 1770–1811) was close to Kant, he wasn't able to publish all of Kant's works. It was simply impossible at the time and, moreover, this project is still in progress today.

LMAVB 413610

In all, Kant taught 268 courses during his long career. Among them, Physical Geography takes third place – he read it 46 times (the first two places are shared by Logic and Metaphysics). Kant was one of the first professors to teach geography, so there were no textbooks. Nor could he draw on his own experience, since Kant spent most of his life in Königsberg. The only source of his knowledge of geography was books and travellers' tales. And although not all of them were reliable and there are some factual errors in Kant's lectures, the result of his work was astonishing. For example, he discovered the mechanism of monsoons and trade winds. Moreover, after years of work, the huge amount of unsystematic information was transformed into a well-structured and easy to understand book.

LMAVB 375155

In 1774, Johann Bernhard Basedow (1724–1790) founded a boarding school in the town of Dessau, Germany, called the Philanthropinum, where children were encouraged to learn better through play rather than punishment. In this school, the teachers paid a lot of attention to cosmopolitan values, exact sciences had an important place and physical activity was of the first importance. Kant was enthusiastic about these new pedagogical ideas and when, in the same year (1774), a course in pedagogy was introduced at the University of Königsberg, he became one of its lecturers. These lectures were later published by one of his students. In this work, the philosopher emphasises that those who reflect on human destiny cannot ignore the problem of education, since it is precisely through education that a person becomes a person

LMAVB 4360338

Kant taught metaphysics according to Alexander Baumgarten's (Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, 1714–1762) textbook, but he eventually changed much of it. The course consisted of six parts: ontology, cosmology, empirical psychology, rational psychology and natural theology. However, it's possible that this book doesn't always reflect Kant's views on these topics, as it was based on the students' lecture notes. Nevertheless, the book can be useful in analysing some ambiguous passages in other works of Kant.